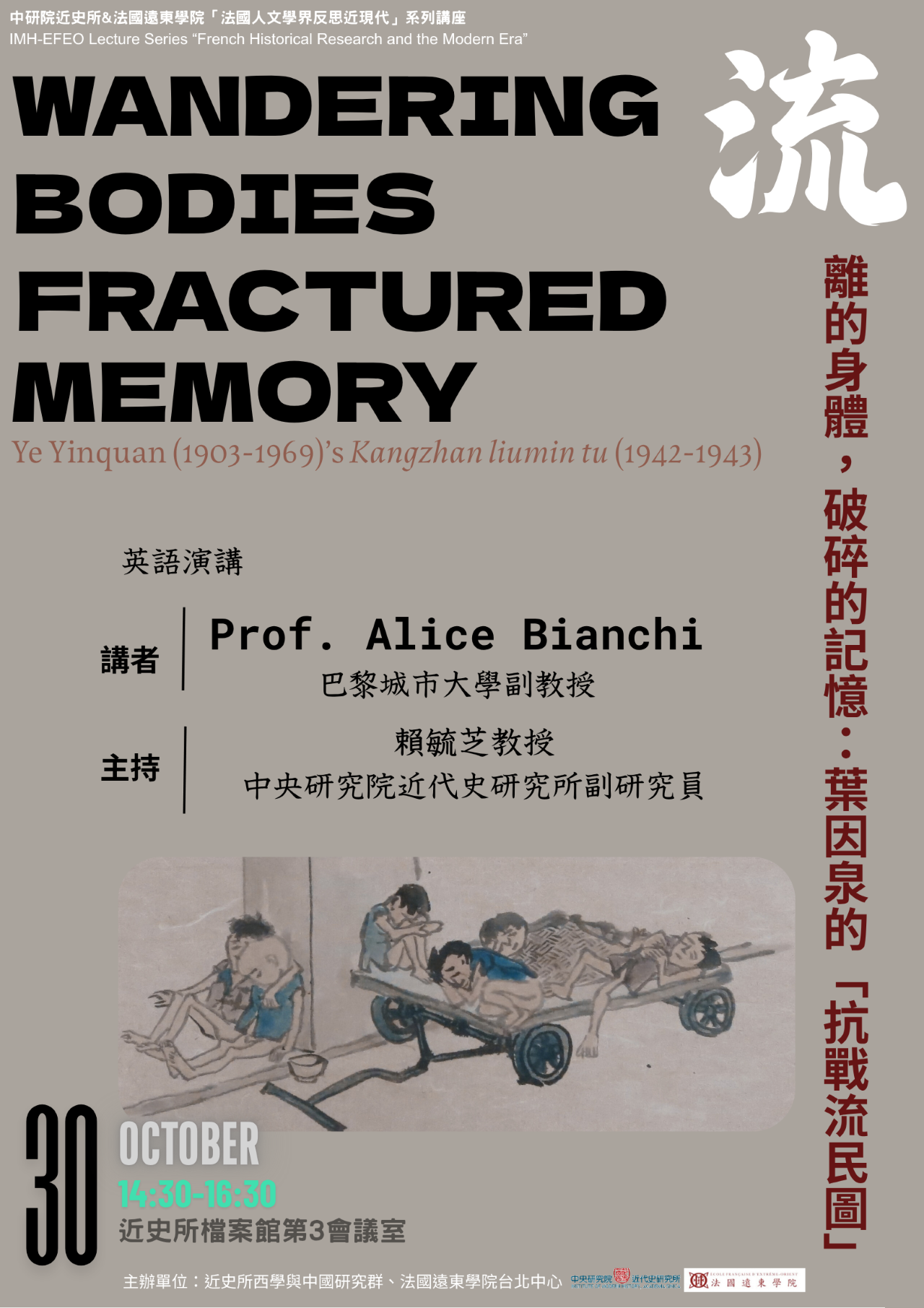

流離的身體,破碎的記憶:葉因泉的《抗戰流民圖》

|

||||||||||||||

摘要:

This talk explores Kangzhan Liumin tu 抗戰流民圖 (Refugees of the Sino-Japanese War), an album of over one hundred paintings created between 1942 and 1943 by Cantonese artist and cartoonist Ye Yinquan 葉因泉 (1903–1969), during his flight from advancing Japanese troops across Guangdong and Guangxi. Based on sketches made during his displacement, the series offers a stark visual account of civilian suffering—particularly the emaciated, vulnerable figures of refugee children, the xiao liumin 小流民, whose hopelessly exposed bodies appear throughout the album. It also includes depictions of guiqiao 歸僑 (repatriated overseas Chinese) and qiaojuan 僑眷 (their families), often rendered with a touch of irony, reflecting the complex social dynamics of wartime South China. While contemporary commentators described the album variously as “a historical painting of the War of Resistance against Japan” (kangzhan qizhong shihua 抗戰期中史畫) or as a form of visual reportage (baodaohua 報導畫), I argue that such labels only partially capture the complexity of Ye’ s visual language—one that blends testimonial urgency with emotional ambiguity, narrative fragmentation, and subtle critique. Combining a deceptively naïve manhua-inspired style with the older Liumin tu 流民圖 tradition —disaster paintings focusing on displacement and famine—Ye moves away from the dominant visual tropes of the Sino-Japanese War, such as propaganda and heroic imagery, to focus instead on the fractured realities of ordinary lives caught between war, hunger, and forced migration. The analysis situates the album within this visual tradition, while also highlighting the innovations that set it apart: its strong regional grounding, its attention to social fragmentation, and its distinctly modern visual idiom.

This talk explores Kangzhan Liumin tu 抗戰流民圖 (Refugees of the Sino-Japanese War), an album of over one hundred paintings created between 1942 and 1943 by Cantonese artist and cartoonist Ye Yinquan 葉因泉 (1903–1969), during his flight from advancing Japanese troops across Guangdong and Guangxi. Based on sketches made during his displacement, the series offers a stark visual account of civilian suffering—particularly the emaciated, vulnerable figures of refugee children, the xiao liumin 小流民, whose hopelessly exposed bodies appear throughout the album. It also includes depictions of guiqiao 歸僑 (repatriated overseas Chinese) and qiaojuan 僑眷 (their families), often rendered with a touch of irony, reflecting the complex social dynamics of wartime South China. While contemporary commentators described the album variously as “a historical painting of the War of Resistance against Japan” (kangzhan qizhong shihua 抗戰期中史畫) or as a form of visual reportage (baodaohua 報導畫), I argue that such labels only partially capture the complexity of Ye’ s visual language—one that blends testimonial urgency with emotional ambiguity, narrative fragmentation, and subtle critique. Combining a deceptively naïve manhua-inspired style with the older Liumin tu 流民圖 tradition —disaster paintings focusing on displacement and famine—Ye moves away from the dominant visual tropes of the Sino-Japanese War, such as propaganda and heroic imagery, to focus instead on the fractured realities of ordinary lives caught between war, hunger, and forced migration. The analysis situates the album within this visual tradition, while also highlighting the innovations that set it apart: its strong regional grounding, its attention to social fragmentation, and its distinctly modern visual idiom.